Can I Make My Own Soy Free Miso Paste?

Soy free miso paste is incredibly easy and safe to make at home. The hardest part is waiting, as miso is one of the longest fermentations.

The high salt content of miso, combined with the fermentation process makes it super safe. The starter cultures, Aspergillus oryzae (Koji), also help ensure that the final product is rich in beneficial microbes that support digestive health.

The Health Benefits of Soy Free Miso Paste

Soy free miso paste is packed with prebiotic, postbiotic, and probiotic benefits that promote a healthy gut microbiome. Since we make miso from beans, it contains prebiotics like fructooligosaccharides (FOS) and galactooligosaccharides (GOS). This balance is essential. A healthy gut microbiome directly affects the gut-brain axis—the communication pathway between the gut and the brain—impacting mood, cognitive function, and overall mental well-being.

Prebiotic Benefits: FOS and GOS in soy-free miso serve as food for beneficial gut bacteria, encouraging their growth and activity. This support enhances digestive health, aids nutrient absorption, and may improve immune function.

Probiotic Benefits: The fermentation process of miso introduces live beneficial microbes, or probiotics, which contribute to gut health. These probiotics assist digestion, help break down food, and may facilitate nutrient absorption.

Postbiotic Benefits: Fermented foods like miso also contain postbiotics, which are byproducts of fermentation that can confer health benefits. Compounds such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) promote gut health by encouraging the growth of beneficial bacteria and reducing inflammation.

The gut-brain axis is increasingly recognized for its role in mental health and cognitive function. By promoting a healthy gut microbiome, soy-free miso may positively influence brain health, potentially aiding mood regulation, stress management, and cognitive function.

Miso is not only a gut-friendly food. Researchers have linked it to a variety of health benefits, especially in relation to longevity. For instance, some studies suggest that miso may aid in the prevention of radiation injury, liver cancer, breast cancer, and intestinal tumors in animal models. (PMC3695331)

This is likely due to the antioxidants and bioactive compounds found in miso. They can help reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are linked to various chronic diseases.

The History of Miso

Different regions of Japan, China, and Korea all make different types of Miso. Some incorporate various local ingredients like barley, brown rice, adzuki beans, mung beans, and even hemp.

Miso, as we know it, originates from Japan. Some scholars think that China or Korea introduced miso to Japan around 600 AD. Many cuisines are flavored with miso, the most popular being Japanese miso soup.

Someone probably made the first miso 10,000 to 5,000 years ago. Scientists think it was first made from fermented grains, shellfish, fish, and meat preserved in salty seawater. Later, it evolved into a product made with beans.

What is Koji—The Miso Microbiome

The important factors that contribute to miso quality and flavor are fermentation temperature, fermentation time, total salt concentration, Koji quality and variety, and substrate used (type of grain or legume used).

In miso fermentation, Koji serves as the starter culture. It consists of rice infused with spores from the Aspergillus oryzae fungus. This fungus plays a crucial role in initiating fermentation. Beyond Koji, the beneficial microbial community in miso typically includes:

- Aspergillus oryzae

- Tetragenococcus halophila

- Enterococcus faecium

- Various species of Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus

Sometimes, Bacillus species are also present, although their growth is controlled by substances produced by Enterococcus faecium. Bacillus prefers environments with 15% to 20% salt concentration and is commonly found on rice, despite not being ideal for miso.

The growth of Aspergillus oryzae depends significantly on the fermentation temperature, thriving best at cooler temperatures around 70°F. Starting miso fermentation in winter and allowing it to progress through spring and summer temperatures promotes different fermentation phases, enhancing the final product.

As fungi, Aspergillus spp. break down their surroundings for nutrients, using enzymes like amylase to decompose organic matter into simpler compounds. These byproducts contribute to digestive health benefits during miso fermentation.

How long is Fermentation for Red Miso?

Red miso fermentation typically takes between 6 to 12 months. It’s similar to the aging process of cheeses and wines—think of it as the difference between fresh, three-month, and cave-aged varieties or the various stages of wine aging.

The preparation of miso itself takes only about two hours of hands-on time, followed by a fermentation period of up to a year. While you can begin tasting and enjoying the miso anywhere between the 6-month and 1-year mark, the flavor continues to evolve and deepen as it ages.

Here’s how the process works:

- Soaking: Begin by soaking the beans for 12 hours.

- Cooking: After soaking, cook the beans until they are soft enough to mash with a fork or potato masher.

- Cooling and Mixing: Allow the beans to cool to room temperature, then mix in the koji and salt.

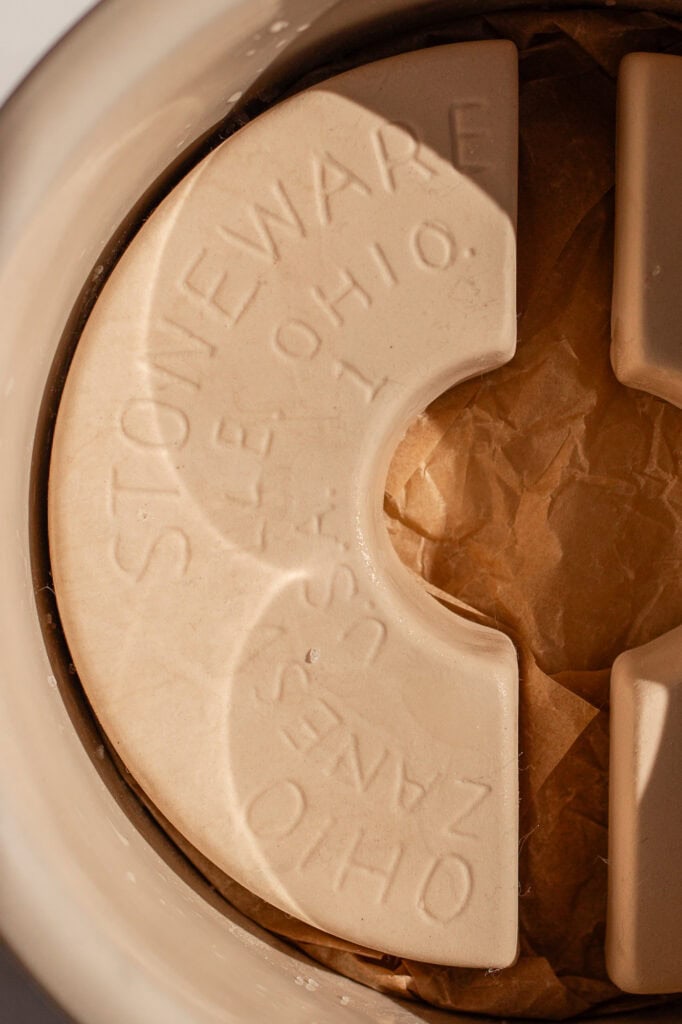

- Packing: Once mixed, pack the miso into a jar, cover it with a layer of salt and plastic wrap or parchement paper, and a lid. Check on it after about three months.

After checking it, the fermentation process will continue for 3 to 9 more months. While I prefer to let my miso ferment for an entire year to develop the most complex flavor, you can jar and refrigerate your miso starting at the 6-month mark if you prefer a younger, milder taste.

Soy Free Miso Paste Recipe Ingredients

Making soy free miso paste is pretty simple; the most crucial step is weighing your ingredients! Here are the ingredients and supplies you’ll need:

- Large glass Jar

- Plastic Wrap

- Sea Salt

- beans

- Koji (Aspergillus orzaye)

- distilled vinegar (for cleaning)

- Kitchen Scale

- Large Bowl

- Potato Masher

(You can also use organic soy beans with this recipe if you want) I love to use Marcella and Mayocoba beans, but you can use any bean or lentil in this recipe. So far, I’ve also tested this recipe with red beans, chickpeas, green lentils, organic soybeans, and black-eyed peas.

Common Questions About Soy Free Miso Paste

Why does my miso smell like alcohol?

If your soy free miso paste has a strong alcohol-like smell, it’s likely due to the fermentation of carbohydrates from the beans. During fermentation, the microbes (including yeasts) break down the sugars in the beans, and one of the byproducts can be alcohol, specifically ethanol.

However, in the case of miso, most of this alcohol is typically converted into acids by the beneficial bacteria, which help develop the signature tangy flavor of the miso. If your miso still has a strong alcoholic odor, it could indicate that too much yeast has been present during fermentation. Yeast can outcompete the other beneficial microbes, resulting in an imbalance.

A strong alcohol smell may also suggest that the fermentation conditions weren’t ideal due to insufficient sanitation or a low salt content.

Does red miso go bad?

Homemade red miso doesn’t really go bad if stored properly. Unlike store-bought miso, which often has an expiration date due to industrial manufacturing and packaging processes, homemade red miso can last for years in the fridge. The reason store-bought miso has a shelf life is because it’s subjected to commercial handling, which can introduce contaminants or affect the product in ways that don’t happen during home fermentation.

As long as you’ve followed clean practices during the preparation and fermentation process, your homemade miso should stay safe and flavorful for a long time. Just be sure to store it in an airtight container in the fridge, and keep an eye out for any signs of contamination or off smells—though this is rare if you maintain proper sanitation. The high salt content of miso acts as a preservative, helping it stay fresh even as it ages.

Can you make miso without Koji?

You can’t make miso without Koji because it is essential for breaking down the beans. Koji, which is made by fermenting rice or barley with the Aspergillus oryzae fungus, produces enzymes that are necessary to break down the complex carbohydrates, proteins, and fats in the beans into simpler compounds. These enzymes, such as amylase and protease, are what enable the beans to ferment properly, creating the rich flavors and beneficial byproducts found in miso. Without Koji, the fermentation process wouldn’t have the necessary enzymatic activity to transform the beans into miso.

Is it worth making your own miso?

Yes! It depends on where you source your koji, salt, and beans, though. On average, it’s much cheaper to make a large batch of miso at home. Store-bought costs about $0.50 per ounce, while homemade costs about $0.39 per ounce.

Does heating miso destroy the probiotics?

Heating miso can destroy some live probiotics since they’re sensitive to high temperatures, typically above 115°F. However, miso still retains many of its nutritional benefits even after heating. While the live probiotics are reduced when cooked, miso still provides amino acids, minerals like calcium and magnesium, antioxidants, and prebiotic compounds such as FOS and GOS. These nutrients remain stable at higher temperatures, so you still get digestive and overall health benefits from heated miso, even without the live bacteria.

More Recipes to try

- Easy Whipped Miso Butter Recipe

- Sourdough Miso Chocolate Chip Cookies with Brown Butter

- Oven-Baked Marinated Chicken Wings with Kimchi and Miso Sauce

How to Make Soy Free Miso Paste (Red Miso Recipe)

Use this comprehensive guide and recipe to learn how to make soy free miso paste! This rich, long-fermented red miso recipe is versatile and can be made with any type of bean, including organic soybeans if you prefer a traditional version.

- Prep: 15 minutes

- Cook: 2 hours

- Total Time: 8738 hours 15 minutes

Ingredients

- 900 grams dry beans (non-GMO, any kind) (1765 grams soaked)

- 500 grams Koji

- 300 grams sea salt

- 50 grams sea salt set aside

Instructions

- Soak 900 grams dry beans overnight for 12 hours.

- Rinse the beans and cook until they are just tender enough to eat. Do not overcook them. When finished, reserve 1/4 cup of bean water and set aside.

- Drain the beans through a colander and allow the beans to cool for 15 minutes.

- Into a large, clean bowl, add the koji, 300 grams of sea salt, and the cooled beans. Mix well using gloved hands or a potato masher. You want to crush all of the beans into a thick paste, kind of like a cookie dough consistency. If the mixture is too dry, add 1 tablespoon of reserved bean water at a time, just enough to get it to stick together a little.

- Prep the jar or container you plan to use as a fermentation vessel. Clean well with soap and hot water, then wipe clean with distilled vinegar.

- Take a large chunk of the miso mixture and form it into a ball with your hands. Then slam the ball into the bottom of the jar. Repeat until all of the miso is in the jar. Press down on the mixture and make sure it’s tampered down.

- Sprinkle the 50 grams of set-aside sea salt across the top of the miso.

- Clean the sides of the jar with a clean cloth dipped in distilled vinegar.

- Place a piece of plastic wrap or parchment paper in the jar, tucking it tightly around the salted top of the miso.

- Place a fermentation weight on top of the plastic wrap/parchment paper and place a lid on the jar. If using a crock, be sure to also use a tight weave cloth secured with twine or a rubber band to keep bugs out.

- Store the miso in a cool dark place for 3 months.

- At the three month mark, check the miso. Remove the plastic wrap/parchment paper, stir and turn the miso, then pack it all back into the jar. Clean the sides of the jar with distilled vinegar, sprinkle a bit more salt across the top and place clean plastic wrap/parchment paper, the weight, and lid back in the jar.

- Allow the miso to ferment for nine more months at a moderate room temperature in a dark cabinet.

- After fermentation is complete, you can transfer to smaller jars and store them in the fridge.

- For a smooth miso paste, blend the miso in a blender/food processor before storing it in the fridge.